return to: vol. 1 front page

Strange Bedfellows:

Sidney Rigdon and the Quincy Whig: 1839-1841

return to: PART II

|

|

return to: vol. 1 front page Strange Bedfellows: Sidney Rigdon and the Quincy Whig: 1839-1841 return to: PART II |

|

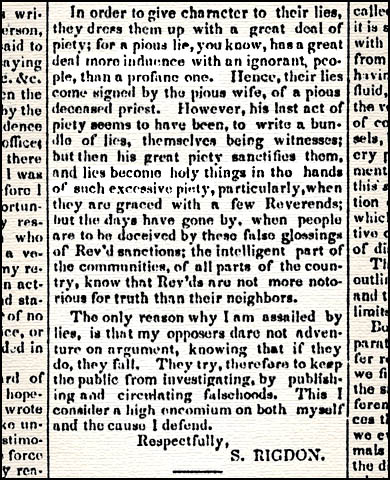

PART III: April 22, 1839 to May 18, 1839 Figure 8: for Chapter 8.

-- Conclusion of Rigdon's May 27, 1839 Letter to the Quincy Whig -- |

|

Chapter 8: Rigdon's Temper Tantrum As previously stated, when Joseph Smith left Quincy on the 18th and started back for Commerce, he probably rode out of town totally unaware of the Matilda Spalding Davison article which appeared in that afternoon's edition of the Quincy Whig. Upon his arrival the next day at the still tiny Mormon headquarters he probably had nothing but good news to report from his trip down into Adams County. Meanwhile the Saints back in Quincy had seen the incriminating article in that Saturday's newspaper and by Monday, at the latest, a copy of the latest Whig was certainly on the road up to Rigdon and Smith. Perhaps by then a copy of the Boston Recorder or some other eastern paper carrying the widow's statement was also well on its way to the Mormon leaders. The following week could not have been a happy one for them. Not only did they now have political and religious fires needing extinguishing in western Illinois, those same kinds of fires were no doubt already spring up all over the eastern mission fields of the Church. Something had to be done quickly to stop the spread of these threatening flames. No record survives to tell exactly when it was that Rigdon and Smith first saw the Matilda Spalding Davison statement in the Quincy Whig. This was obviously not a matter which the Mormon leaders discussed openly with the small band of their followers who were beginning to congregate around the little hamlet of Commerce. Thus, any attempt to reconstruct their actions and reactions in late May, 1839 must necessarily involve a certain amount of guesswork. It is entirely possible that the Matilda Spalding Davison statement did not reach the Mormon leaders until nearly the last week of the month. And it is perhaps even possible that the Smith brothers knew little of the matter or for some other reason left it in Rigdon's hands when it first came to their attention. All that can be said with any confidence about the sequence of events is that by May 27, Sidney Rigdon was writing a scathing reply which he intended to see published as soon as possible in the Whig. "A pious lie, you know, has a great deal more influence with an ignorant people, than a profane one."Of course this whole question of Book of Mormon origins and Rigdon's purported secret involvement with the bringing forth of that book (as well as his alleged role in very the foundation of Mormonism itself) was no new threat to the Latter Day Saints. Sidney Rigdon and Joseph Smith had faced essentially the same charges back in Kirtland, Ohio between 1832 and 1837 and they had there succeeded in sidestepping any slings and arrows which could have wrought permanent damage to the Church and its leadership. In Ohio the whole problem appeared to hinge upon one or two bitter apostates from Mormonism allying themselves with the resident anti-Mormon forces to invent and publish "moonshine stories" saying Sidney Rigdon had compiled the Book of Mormon from the writings of some dead clergyman. These traitorous tales may have been temporary irritants for scripture-thumping Mormon missionaries wandering the southern shores of Lake Erie in days gone by, but they posed no lasting peril to the "chosen people" -- or so said the priests of the Church of Latter Day Saints. However, this new accusation so conscientiously passed along by the champions of candor at the Quincy Whig was quite a different matters. This was no witches' brew served up by recreant backsliders cut off from the "one true church;" this was the purported statement of an elderly and godly lady held in esteem by the Congregational Church. This revered dame of seventy summers seemed an unlikely foe of the Saints; sitting in her tidy parlor in southern Massachusetts and reminiscing about her late and reverend husband, the chronicler of wonderful old legends. But, just because such a prim old grandmother was an such unlikely perjurer, she was all the more an inherent menace to the firm of Sidney Rigdon & Associates, Ltd., purveyors of gilt-edged holy books extraordinaire. Now the press of Bartlett and Sullivan was informing everyone from Governor Carlin down to the ticket-takers at the ferry dockside that this respectible old widow's husband was the original biographer of fictional old Prophet Mormon himself. Here was a new and dangerous challenge to their authority which the churchly brethren could afford neither to ignore out of hand, nor to combat with the second-rate sneers generally reserved for their apostates. This matter demanded Rigdon and Smith's immediate attention and their most consummate skill in defending the faith. Yet the erratic Great Baptizer and his clairvoyant chief seemed strangely unable to rise resplendently to the critical challenge now before them. Sidney Rigdon, May 27, 1839. One of Rigdon's early biographers, the Rev. William H. Whitsitt, was profoundly skeptical that the widow's statement of 1839 was entirely a product of her own creation. And, in fact, both Whitsitt and numerous Mormon apologists writing over the years have raised many legitimate questions as to how much of that 1839 testimony can be reasonably traced back to the widow herself. Certain parts of the 1839 article are obviously attributable to an editorial pen, and also to some clumsy misquotation from some person who had glanced through Eber D. Howe's 1834 Mormonism Unvailed, the book which first publicized the Spalding authorship claims and which first accused Rigdon of turning Spalding's writings into latter day pseudo-scripture. But, writing from Commerce on May 27, 1839, Sidney Rigdon was obviously in no state of mind to trouble himself very long with such minor details. His reaction, first and foremost, was to brand the entire production attributed to Spalding's widow a "batch of lies." As Rigdon explained the matter, the widow's supposed statement originated out of the despicable machinations of her late husband, a backslidden clergyman whose only claim to fame was that he was a a great liar. I Rigdon's estimation, this "creature," Solomon Spalding, had done nothing more than produce a "a bundle of lies" in his lifetime. And those pious falsehoods, those "lying scribblings," were doubly inappropriate as a production from "a man of the cloth" because they were written down solely for "the purpose of getting money." In other words, the dead clergyman was a priestcrafter who probably wrote his sermons to cheat parishinors out of their hard-earned dollars and who likewise wrote some worthless scriptural-sounding rant for the same ungodly purpose. Somewhere along the way the Rev. Spalding had neglected to teach "his pious wife not to lie," and that was the long and the short of it "In order to give character to their lies, they dress them up with a great deal of peity..."At first glance Rigdon appears to have been simply shouting the word "lies" over and over with no particular method in his mania. But a close inspection of the article he was rebutting uncovers the root cause of his rabid response. That original published statement had declared that "Sidney Rigdon... [was] connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson... as Rigdon himself has frequently stated." When Rigdon read those lines in the widow's statement be instantly knew he had before him a sterling example of the very sort of "lie" he so vociferously rants about throughout his rebuttal letter. The quoted passage, inferring that Rigdon had once been employed in a Pittsburgh "printing office of Mr. Patterson" was a poorly written attempt to reproduce an assertion printed in Howe's book nearly five years before. What Howe had really said back in 1834 was that Rigdon "was... seen frequently in his [Mr. Patterson's] shop. Rigdon resided in Pittsburgh... as he has since frequently asserted." This blundering paraphrase of Howe may or may not have been voiced by Spalding's widow, but it is most likely an editorial insertion made by a certain D. R. Austin. Austin played the role of middleman in getting the widow's statement set down in writing and submitted to the newspaper and a certain portion of its content is probably more of a summary of what he heard from her than a perfect transcription of her words. Whitsitt offers these remarks in regard to Rigdon's motive and reaction: Howe had struck the mark so accurately in his publication of 1834 that Rigdon was overwhelmed; throughout the intervening five years he had writhed in silence under the justice and the severity of the blow, without daring anywhere to commit a reply to print. But when the clumsy fabrication that bore the signature of Mrs. Spaulding Davison was given to the public, he immediately perceived that his opponents had given him an opportunity that had been sadly lacking heretofore to deny something. He now had a grievance and hastened to give it air with a fine display of his best "plantation manners." His letter in reply was dated Commerce (Nauvoo), May 27th 1839... Rigdon's Rude Remarks: or, "negroes who wear white skins" Actually, Whitsitt was not strictly correct in his claim that Rigdon had been totally silent in public since the publication of Howe's book, not "daring anywhere to commit a reply to print" to the claims printed by Mr. Howe. In fact, much of the content of Rigdon's letter of May 27, 1839 bears a strange resemblance to another letter printed just the year before by the LDS Church's own official newspaper. But Whitsitt's observation, that Rigdon had been given "an opportunity... to deny something," is right on the mark. While Rigdon had doubtlessly been in Pittsburgh many times in his youth, he almost certainly had never been employed by either the Rev. Robert Patterson, Sr. or his brother and business partner, Joseph Patterson. Jr. That much Rigdon could deny with impunity, as loudly as he cared to broadcast it from the housetops. As for neither of the Patterson brothers ever owning a printing office in Pittsburgh, so long as Rigdon lived withing walking distance of the town; that was a bit of a fib in the mouth of the Mormon. Robert Patterson, Sr. was for a lengthy period of time engaged in printing and selling reading matter in Pittsburgh. In some years he may have contracted a printing press rather than own one. In other years the press may have been directly under his control and located within a stone's throw of his office desk. Depending on which years between 1812 and 1825 Rigdon cared to admit being in Pittsburgh, his hair-splitting over Patterson's having a "printing office" may have been more or less believable. At any rate, Patterson knew Rigdon, Rigdon knew Patterson, and neither of the two ever said Sidney ever drew a salary from the Pittsburgh bookman. The Great Orator of the Western Reserve could orate with justified, self-righteous indignation that he had never, ever "frequently stated" that he had been connecetd with Patterson's bookish operations. As for rebuking the many demons emanating from Howe's 1834 book, the Mormon Brethren had printed, here and there, now and again, a few small items which functioned as semi-refutations to the several accusations made against them and their scriptures. Rigdon certainly had some hand (either in writing or in approving) these snippets of apologetic. But the one example of anti-Howe rhetoric which most closely approximates the invective of his May 27th missive was an interesting editorial which had appeared only ten months before in the final issue of Joseph Smith's own Elders' Journal, published at Far West, Missouri: One thing we have learned that there are negroes who wear white skins as well as those who wear black ones.... no sooner were they excluded from the fellowship of the Church and gave loose to all kind of abominations, swearing, lying, cheating, swindling, drinking with every species of debauchery...Although attributed to Elders' Journal editor Joseph Smith, Mr. Rigdon was the likely ghost writer for a good deal of the purple prose appearing in Smith's periodical. In the passage above the Mormon maharajas of Far West are venting their spleens just a bit in regard to those wicked apostates of lakeshore Ohio, the ones who dared dangle the keys to the Kirtland Temple from the belts and style themselves the "pure" Church of Christ. And as it is with these pathetic "creatures," so also it was with the likes of Eber D. Howe and Doctor Philastus Hurlburt, the 1838 apostates' neighbors and recent partners in perfidy. The Elders' Journal editorial continues: As it was with Doctor Philastes Hurlburt, so it is with these creatures. While Hurlburt was held in bounds by the Church and made to [behave] himself, he was denounced by the priests as one of the worst of men, but no sooner was he excluded from the Church for adultery, than instantly he became one of the finest men in the world. Old deacon Clapp of Mentor ran and took him and his family into the house with himself and so exceedingly was he pleased with him, that purely out of respect to him, he went to bed to his wife. This great kindness and respect Hurlburt did not feel just so well about but the pious old deacon gave him a hundred dollars and a yoke of oxen, and all was well again. This is the Hurlburt that was author of a book which bears the name of E. D. Howe, but it was this said Hurlburt that was the author of it. But after the affair of Hurlburt's wife and the pious old deacon, the persecutors thought it better to put some other name as author to their book than Hurlburt, so E. D. Howe substituted his name. The change however was not much better. Asahel Howe, one of E. D.'s brothers who was said to be the likeliest of the family, served apprenticeship in the work house in Ohio for robbing the post office.... Hurlburt and the Howes are among the basest of mankind...While writers like Whitsitt might argue that this text, appearing in an editorial notice "To the Subscribers of the Journal," says nothing of Rigdon or the Spalding claims for Book of Mormon authorship, a closer inspection of its contents and concerns will tell differently. While it is possible that Elders' Journal editor, Joseph Smith, wrote the above lines about "negroes who wear white skins," apostate Mormons in Geauga Co., Ohio who were supporters of "all kind[s] of abominations, swearing, lying, cheating, swindling, drinking with every species of debauchery," and persons like Eber D. Howe and D. Philastus Hurlbut, "the basest of mankind," it is just as likely that Smith delegated the writing of these particular sentences to "high-faluting Sidney Rigdon," Smith's old mentor and a man who well knew his way around all the ins and outs of bombastic rhetoric. And, while the Spalding claims for Book of Mormon authorship are nowhere mentioned here specifically, the demonization of Hurlbut and Howe renders that whole point moot. If this researcher and his publisher companion were "the basest of mankind," it might well be argued that there was no use in readers (Mormon or otherwise) wasting their time examining the probable lies of anti-Mormons who might do anything under the sun to try and discredit the Church of the Latter Day Saints. This kind of a refutation for the claims of Hurlbut and Howe had made in Ohio may have flown breezily from the Mormon flagpole at Far West in 1838. There Smith and Rigdon were writing and publishing a little newspaper which circulated almost exclusively among their faithful followers. But when Rigdon attempted to hoist this slogan emblazoned banner among the Gentiles of Quincy the following year, it brought only sighs of distaste and embarrassment from the Whig's readers. In his May 27, 1839 letter Rigdon essentially retold the same dirty story about Hurlbut's wife and declared that the man who had first put the Spalding claims before the public was not to be trusted in anything he did or said. Rigdon's equally sinister attempts to assassinate the character of Solomon Spalding and Spalding's widow also fell upon the deaf ears of Quincy's non-Mormon citizens. Although the plight of the fugitive Saints had brought forth genuine compassion and charity from the "suckers" of riverside Illinois, Rigdon's demonization of elderly Protestant ladies and deceased Protestant clergyman was not the sort of thing the Quincyites relished reading in their Saturday papers. Could the writer of this vile letter possibly be the far-famed, eloquent spokesman of the Latter Day Saints, the same Rev. Mr. Sidney Rigdon whom Democratic state legislators and governors had praised as being a man of highest honor in their recently composed letters of recommendation to the President and Congress of the United States? Surely something was wrong here! Of course what was wrong was that the mentally ill Rigdon had suffered yet another of his manic, paranoid episodes and in the throes of that cerebral anguish had authored a most unflattering epistle which should have never been submitted to a Gentile newspaper in western Illinois. It is a wonder that Joseph Smith did not have the foresight to censor the production immediately. But then, perhaps Smith did not even see the letter of response until it was published, or, if he did read it through, perhaps he had become just as insensitive regarding proper manners among the Gentiles as had his volatile counselor in the LDS presidency. At any rate, Rigdon's letter was received in Quincy, published on June 8, 1839, and quickly brought this response from a non-Mormon reader: From the only construction I can put upon his {Rigdon's] writing, it seems that all who are opposed to Mormonism are "liars," and their sayings "lies." He has certainly mistaken the character of the western people, if he supposes he can force such a thing upon them for truth, merely by the repetition of his favorite phrase liars and lies. Suckers can swallow almost any digestable matter, but they never can swallow this, especially when they have opened their doors, replenished their tables, and welcomed the needy Mormons to the comforts of life. What, all are liars! merely because they cannot believe the absurdities of this new ism. Almost every person who comes under his notice is a desperado -- no respect to either sex of whatever age, neither of the dead nor the living. Such is the production of one of the head men of that sect who have cryed so loud for our piety and our hospitality... A Still More Uncourteous Character The kind of popular reaction Rigdon was generating, be it from Democrat or from Whig, was precisely the kind of publicity and reproof that the Mormons did NOT need at such a critical juncture in their reorganization as a holy people in Illinois. And it is supposed that Joseph Smith acted quickly to nip these wild thorns of journalism in the bud. As for Rigdon, he was still in a high state of agitation as late as the end of June. Firing off yet another self-protective missive to the Whig at that time, the paroxysms of this highly stationed man of God were countered with a few lines of dismissive condescension from Bartlett and Sullivan: Mr. Rigdon has sent us a communication intended as a reply to the queries propounded by a correspondent two weeks since... Mr. Rigdon will perceive from a little reflection, that it could answer no good purpose by publishing his communication -- it would of necessity, call forth a rejoinder of a still more uncourteous character... We consider it best... to close the door upon this controversy.How quickly Sidney Rigdon had squandered the priceless capital of good repute and Gentile assistance he had accumulated almost by default when he had first arrived in Quincy only three and a half months before. He still had his letters of recommendation to the President and Congress in his back pocket, but of what value were all those fancy laudations, now that the second highest of all Mormon leaders had been lectured up upstart Whig journalists as though he were a naughty schoolboy, caught in the act of cursing in the classroom? Rigdon's name, which had so often graced the columns of the Whig and the Argus was now destined to become a little seen anomaly in their pages. When his name is next encountered in the Whig it merits but a single sentence in the context of a little notice regarding the laying of the cornerstone for the Nauvoo Temple in April of 1841. After that the once acclaimed Mormon leader, Sidney Rigdon, is but a "P.M." (postmaster), sending in lists of names from the dead letter stacks in Nauvoo, hoping to collect a few meager cents now and then on the postage due for those unclaimed letters. Four decades later, Wilhelm R. von Wymetal would sum up Rigdon's humble station in Nauvoo thusly: But where is President Rigdon, my servant Sidney, always named first in the early revelations of the Lord? Where is the Lord's Messenger and Mouthpiece, the inspired projector, architect and great Messianic feetwasher of the Kirtland temple, the great interpreter of the Nephite, and scores of other records and tongues? He is nowhere... You see him in a poor little office, a log shanty, probably, the Lord's postmaster; but only a postmaster after all. How are the mighty fallen... He was an excellent fellow for expounding the new gospel on Sundays, but he was no practical kingdom-builder, no business-man.... Religion is all very well for the people, but look at the Jesuits; they are men of the world, the friends, and advisers of emperors and kings; that's what we want now -- "mark it, Elder Rigdon." | ||

Chapter 9: Aftermath: Alexander Badlam's Letter Revised text, footnotes, and appendices will be re-posted shortly.) The xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxx x x xxx x xx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx x x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxx |